What is a SPRINT?

How Big Problems and Little Time Lead to Great Solutions

A sprint is something runners do. For them, all that matters is getting to the end as fast as possible. The sprint process has a similar goal: get a business to a feasible solution in a short amount of time.

Although it seems like businesses are more complex and could not simply solve a problem in a week, the sprint method has been tested over more than a decade and shown impressive results.

In their book SPRINT: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days, Knapp and his colleagues Braden Kowitz and John Zeratsky describe how they developed the sprint method and use it to help businesses solve problems efficiently.

Origin of the Sprint

Jake Knapp created the sprint method of problem-solving while working for Google in 2012. He first experimented with what became the sprint when he realized that “the ideas that went on to launch and become successful were not generated in the shout-out-loud brainstorms” but rather came from the regular places people got ideas - “while sitting at their desks, or waiting at a coffee shop, or taking a shower. Those individual-generated ideas were better. When the excitement of the workshop was over, the brainstorm ideas just couldn’t compete” (Knapp, Jake, et al. 2).

When the excitement of the workshop was over, the brainstorm ideas just couldn’t compete

Knapp realized his best work had come from moments when he had a big challenge in a small amount of time. He decided to take what he learned and try a new workshop he called a “sprint.” It worked, and the process spread throughout the Google offices. A few years later, Knapp met with Bill Maris, CEO of Google’s venture capital firm Google Ventures, who convinced him to utilize the sprint method for startup companies (Knapp, Jake, et al. 4).

Since then, Knapp’s book has spread the sprint far beyond Google, and it has become a trusted process for effective solutions in minimal time.

The Sprint Structure

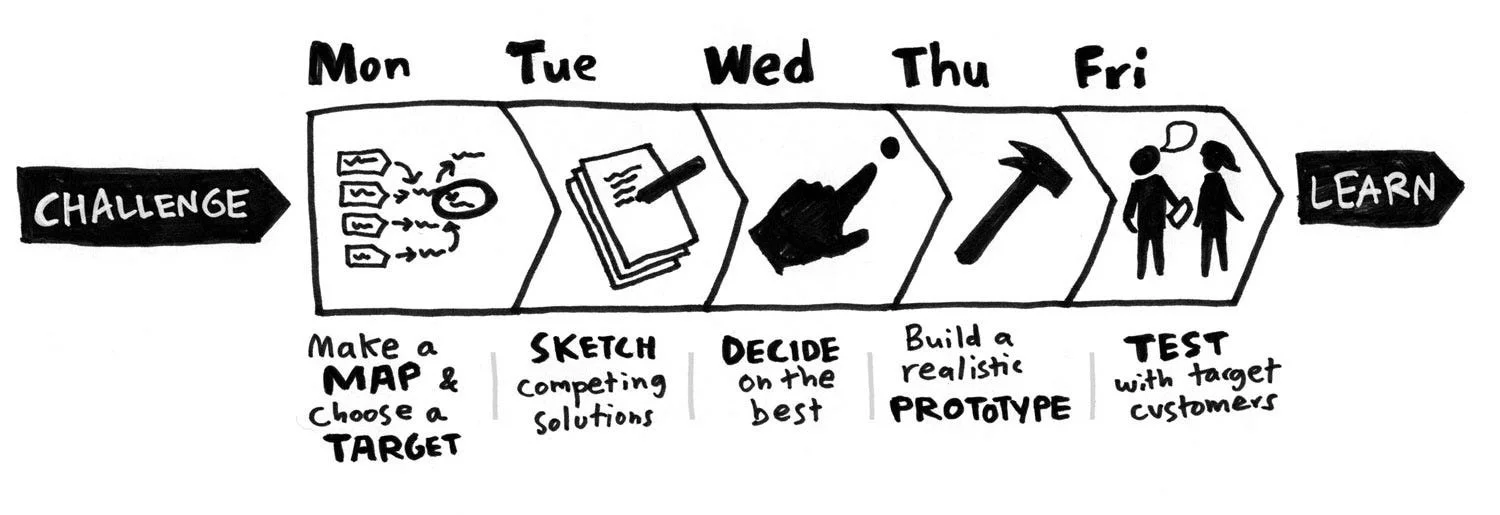

With only five days to come up with a testable prototype, sprints have to be precisely structured and controlled to stay on track. Each day is designated a certain goal that sets the team up for the next step in the process.

“On Monday, you’ll map out the problem and pick an important place to focus. On Tuesday, you’ll sketch competing solutions on paper. On Wednesday, you’ll make difficult decisions and turn your ideas into a testable hypothesis. On Thursday, you’ll hammer out a realistic prototype. And on Friday, you’ll test it with real live humans” (Knapp, Jake, et al. 16).

Sprint structure, credit Jake Knapp

Benefits of a Sprint

How does rushing lead to good results? How can solutions emerge in such a short period of time?

When Knapp first realized that challenges with not enough time led to his best results, he compared them to his previous workshops.

He says, “What was different?

First, there was time to develop ideas independently, unlike the shouting and pitching in a group brainstorm. But there wasn’t too much time. Looming deadlines forced me to focus. I couldn’t afford to over-think details or get caught up in other, less important work, as I often did on regular workdays” (Knapp, Jake, et al. 3).

By compressing the work into just one week, people are forced to focus on what is most important. They can’t afford to waste time on small or insignificant details and quickly learn what is actually necessary for the goal. The essential parts emerge, leaving the rest to be dealt with when the foundation is established.

First, there was time to develop ideas independently […] But there wasn’t too much time

Knapp continues and says, “The other key ingredients were the people. The engineers, the product manager, and the designer were all in the room together, each solving his or her own part of the problem, each ready to answer the others’ questions” (Knapp, Jake, et al. 3).

Rather than being disjointed with different branches and offices trying to communicate, sprints gather all the necessary people in one place to share their expertise and perspective on the situation.

As Knapp says, “In most organizations, it would take weeks of meetings and endless emails to decide. But we had a single day. Friday’s test was looming, and everybody could sense it. We used voting and structured discussion to decide quickly, quietly, and without argument” (Knapp, Jake, et al. 11).

In most organizations, it would take weeks of meetings and endless emails to decide. But we had a single day

The condensed timeline of a sprint leads to a basic prototype the team can test. By creating this “surface” of a finished product, companies can see how customers interact with it. This saves the time, energy, and money that would have gone into an actual product they couldn’t be sure people would actually like.

Knapp et al. says, “When our new ideas fail, it’s usually because we were overconfident about how well customers would understand and how much they would care. Get that surface right, and you can work backward to figure out the underlying systems or technology. Focusing on the surface allows you to move fast and answer big questions before you commit to execution, which is why any challenge, no matter how large, can benefit from a sprint” (Knapp, Jake, et al. 28).

By reducing problems to the essentials and creating testable prototypes without the resource investment, sprints allow teams to tackle any size problem. They ensure time and energy efficiency by concentrating the process into a week. From their original source of one Google engineer, the sprint has become a proven and trusted method for businesses to confront problems, find solutions, and plan a path for success.

Sources:

Knapp, Jake, et al. SPRINT: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days Bantam Press, 2016.